SYNOPSIS | BURNING MAN | DIRECTOR’s NOTE | BACKGROUND | ARTIST LETTERS

5 years of research, filming and interviewing many people involved with Burning Man, I’m happy to announce the documentary is done, and started screening in March 2009.

Film Synopsis: Dust & Illusions explores 30 years of history of the Burning Man event. Born in the underground of San Francisco in the 1980s, the festival became the largest counter- cultural event in North America. It is unique in that it is created by the people who come to the event, the participants, not the organizers, and in that sense it has survived its original ideals/utopias, but the ideas have been eroded by time, pressure from the larger society. The film is a look at this necessary evolution and expansion and questions our ability to stand behind those ideals over a lifetime.

About Burning Man: Burning Man started officially in 1986, on a god-like vision of Larry Harvey… well at least that’s what he says. Harvey had been living a pretty hermit like life with his girlfriend in Oregon until 1978 when he moved to San Francisco. There he met diverse groups of creative people, that certainly influenced him to go down to Baker beach with his friend Jerry James and other carpenters and burn the first little Wicker Man like effigy (he will deny the Wicker Man origins, but that’s the version I personally prefer).

About Burning Man: Burning Man started officially in 1986, on a god-like vision of Larry Harvey… well at least that’s what he says. Harvey had been living a pretty hermit like life with his girlfriend in Oregon until 1978 when he moved to San Francisco. There he met diverse groups of creative people, that certainly influenced him to go down to Baker beach with his friend Jerry James and other carpenters and burn the first little Wicker Man like effigy (he will deny the Wicker Man origins, but that’s the version I personally prefer).

Later on the event kept happening on Baker Beach until 1990, where police stopped them from burning it. The San Francisco Cacophony Society was organizing a Zone Trip (excursion of their own) to the Black Rock Desert 2 months later and invited the Burning Man to come with them on Labor Day of 1990 (September). There were 89 people.

Eventually the little gathering grew into a large scale festival, that features a large amount of Art specifically built for the event by people from all over the world, but mostly within the United States. Nowadays what makes the event still unique is its location (the Black Rock desert is a federally protected natural preserve 200km from the first city Reno), its concept (the organizers take care of the legal permits, the infrastructure, but do not bring any of the Art and entertainment available during the event. That is brought by the participants themselves to their own costs) and its length (it goes on for 8 full days).

Director’s Note: I discovered Burning Man in 2003. I had lived in San Francisco for 5 years at that point, and had heard about the event, and the general accounts sounded like “It’s the most amazing experience you’ll ever have”, “It has changed my life”, “It’s a wild decadent party”… Born in France, I had a hard time to believe the first two about a one-week festival in the desert. I always thought that things that change your life are not a single event in your life but rather they’re based on a long process – which we might not always be aware of. And after 5 years in the USA, I also started to have a good understanding of how always mesmerized Americans, at least the ones from the San Francisco area, seem to be about everything. Always genuinely exaggerating. On the other hand I had no doubt that a festival with 40 or 50,000 in the middle of desert could degenerate into a wild decadent party.

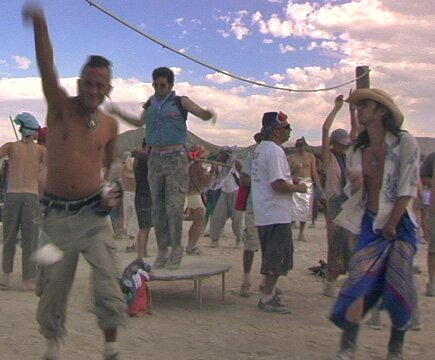

So in 2003, I finally decided to go, and see for myself what kind of life changing experience the desert party really was. I packed some food, a tent, and went off 6 hours away from San Francisco. When I started to see the city, 10 miles away, emerging from the desert floor, it looked like Mad Max. Literally. A flat piece of earth, with dust plumes rising high above the ground, and a massive encampment in the middle of it. It was a very surreal vision. How could a place like that really exist? Once I entered the festival, it still looked like Mad Max with all these tents and shade structures, and sometimes a vehicle that resembled a space ship, or a simple couch on wheels. People appeared as if they had been residing there for a while, and for some, as if they had lost their mind. Indeed, decadent, but more like the end of a civilization. After a few days, I started to have a better feel for this city in the dust. People had come here, and for the most part set up camps to party, drink or do some yoga. Some were more elaborate than others, but in general, it seemed like a lot of money had been thrown into the camps. Based on the festival rules, no money could be exchanged here, and those who came prepared were here to give away their drinks, massages, and music 24/7.

So in 2003, I finally decided to go, and see for myself what kind of life changing experience the desert party really was. I packed some food, a tent, and went off 6 hours away from San Francisco. When I started to see the city, 10 miles away, emerging from the desert floor, it looked like Mad Max. Literally. A flat piece of earth, with dust plumes rising high above the ground, and a massive encampment in the middle of it. It was a very surreal vision. How could a place like that really exist? Once I entered the festival, it still looked like Mad Max with all these tents and shade structures, and sometimes a vehicle that resembled a space ship, or a simple couch on wheels. People appeared as if they had been residing there for a while, and for some, as if they had lost their mind. Indeed, decadent, but more like the end of a civilization. After a few days, I started to have a better feel for this city in the dust. People had come here, and for the most part set up camps to party, drink or do some yoga. Some were more elaborate than others, but in general, it seemed like a lot of money had been thrown into the camps. Based on the festival rules, no money could be exchanged here, and those who came prepared were here to give away their drinks, massages, and music 24/7.

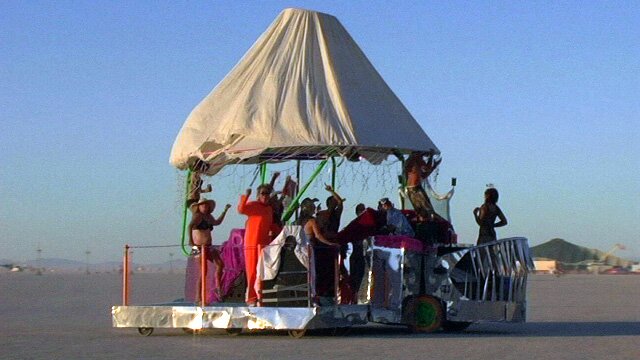

In the end, Burning Man is different from other festivals because the attendees are the ones providing the entertainment, not the organizers. It gives a strong sense of freedom, since anyone can make anything happen. But a party remains a party, and quickly the original curiosity softens out. One aspect, though, made the festival really unique: the Art. Outside the boundaries of the encampment, in the open desert, lied around some pretty impressive sculptures. With the desert floor as a canvas, the mountains as the frame, the place  was transformed into a gigantic museum, where the artwork was left to the madness of the participants and the natural forces. That museum appeared like nature had ripped its walls down, and there were left the pieces of the last exhibition. Again, it felt like civilization had just ended, although, quickly enough, an ambulant rave party would come cruising by merely using the artwork as a reference point in their journey to nowhere.

was transformed into a gigantic museum, where the artwork was left to the madness of the participants and the natural forces. That museum appeared like nature had ripped its walls down, and there were left the pieces of the last exhibition. Again, it felt like civilization had just ended, although, quickly enough, an ambulant rave party would come cruising by merely using the artwork as a reference point in their journey to nowhere.

When I came back to San Francisco, I decided to learn more about the organizers and the artists responsible for this extravagant gathering. It took me 3 years to discover everything that I know about Burning Man today. Very early on, I was lucky enough to be introduced to Flash who has been a very close friend of Larry Harvey, the main founder of the event, since Larry’s arrived in San Francisco in 1980 and I have lived quite a few adventure with him and others, allowing me to get pretty intimate with some historically important figures of the festival. In 2004, I also joined the Flaming Lotus Girls, one of the emblematic groups of artists who have produced impressive sculptures of metal that spits large amounts of fire for the festival. My participation in their group allowed meeting many other artists and active participants as well as people involved in the organization of the event.

During those 3 years, most of these characters have shared with me the stories that have made their lives and the history of the event, and of its deep origins in the counter-cultural movements of the late 70s and 80s in San Francisco. It was only in this manner that all 22 interviewees that make the documentary, opened up to my “intrusive” questions, my provocations and questioning of their beliefs and culture, allowing for an in-depth look at the birth and rise of one of the major counter-cultural event in North America of the past 30 years.

The documentary is a look at another attempt to create a community with more humane values, and how hard it is to escape the system of the larger world we live in. There’s a little bit of hope, though, through the portrait of the artists that truly make the event unique. For them the weeklong festival is like a wink of the eye, since groups like the Flaming Lotus Girls spend the other 51 weeks of the year creating their artwork, and there, in their collaboration, they find the social connections we seem to miss more and more.

Background on how the film was made:

Burning Man is unique to me in the sense that everything you find at the event is made by the people who come to it, and actually pay their own ticket. The organizers make sure to get the permits, and set up a minimal infrastructure, such as supply bathrooms, security, medical tents, and also bring all sort of machinery to help people build their art and their gigantic camps.

Artists building their art

When I started the documentary I met many groups of artists, building giant sculptures for Burning Man. They would often get together months, sometimes even a year in advance, to design, gather the materials, meet to decide, organize fundraisers, and build a piece of art that would most certainly only be seen once at Burning Man. And some groups like in the 2 left pictures above would build giant sculptures of wood, temples, to burn them down at the end of the event. The people behind the art would often not be full time artists, they would have a regular job, and work at nights and weekends for a full year with no other goal than to blow the mind of others and certainly theirs. I was mesmerized by the energy, and the will to create art only for the sake to create art, and often share it once for a single week.

After my first year, I decided to make a documentary… because the story needed to be told. But Burning Man beyond the art, is like a free, open-minded community that comes here for a week to let go of many hang-ups that we all have and that builds up throughout time, and coming around with a video camera is not really considered a good thing. People come here to be free of the everyday world, and express that freedom in many different ways, that often needs the voyeuristic eye of the camera to be away, in order for the freedom to be complete.

It became obvious that I had to make my camera work as integrated as possible in the Burning Man experience, to avoid interfering with anyone’s experience. I wanted to become one of the builders, one of the artists of that community. And I was going to try to do it with a camera.

A few months in the process, I decided to film a lot more than what I needed to produce the documentary with, and actually to follow groups of artists throughout an entire project, and then give them all the footage that I had for their own usage… do whatever you want with my footage, since it’s about what you have sweated over for the past year. My contribution is small in comparison…

The funny thing that happened through becoming part of these groups of artist is that I discovered the other side of Burning Man. I discovered what it takes for the artists and the organizers to put the event together, but I also discovered the politics, I discovered the battle for power, the real relationships that existed between the people who were so deeply involved with the event. As I was experiencing completely how creating and organizing was the key to building a true community of people, I was also seeing how that couldn’t be without some people imposing themselves over others, and naturally pushing some away no matter how creative they could be!

That became the story I wanted to tell… the story of a community that built itself over 30 years, since its origins in the late 1970s, and how it dealt with its exponential growth. That is DUST & ILLUSIONS. The visual Illusions that the desert creates through its many weather patterns, the Illusions created through the many states of the mind everyone goes into there, and I ask: maybe the Illusions that what we’re doing in the desert and year around is really different from the way our larger society functions.

Hope to see you soon at a screening to talk more about these things and others.

Olivier Bonin, Director.

ARTISTS’ LETTERS

Below you will find some testimonials that some of those artists have written for me. I asked them to write a small letter in order to help me convince the Burning Man organization to publish a request for support in their massive newsletter (called the Jack Rabbit Speaks – JRS) that goes to thousands of people.